Roberta Oloyade Stokes

Roberta Oloyade is an activist, educator, healer, musician and an early member of Salsa Soul Sisters (the oldest black lesbian organization in the United States). Across all of the dynamic aspects of her practice, Roberta has fought for empowerment for lesbian and queer women of color. Her emphasis on authentic self-expression, communication and friendship has enabled countless women to come out of the closet in a safe way and to build meaningful and productive lives. The following conversation was recorded on March 31, 2020 at 1pm by phone in New York, NY.

Gwen Shockey: The first question I’ve been asking is if you can remember the first place you ever were that was occupied mostly by queer women or lesbians and what it felt like to be there.

Roberta Oloyade Stokes: Interestingly enough I was actually in Ibiza on Balearic Island in Spain as a teenager. We didn’t have any clubs at all growing up. We had house parties. They weren’t so specific. Everyone was in those parties. You know? I’ve been in the life my whole life. At seven years old I knew. I had the same girlfriend from seven to eighteen years old. So, if any of us had a party the whole neighborhood was there. So, being in a place that was like all queer… it was amazing. Ibiza is an island in Spain. They had a club called Lola’s. I think I had just turned eighteen when I had gone there. I had gone to do a work-study in Barcelona but everybody was talking about this little island where you could be free and party. They had a specific club for women there. The boys club became kind of a club for everybody but the women wanted a club where specifically women could come in, which was great, because I always had a challenge in New York going to certain clubs. I didn’t always like the mix. Places at that time, even if we had camaraderie going on with the guys, they still didn’t really like women and they’d speak to the women in a certain kind of way. Later down the line of course we had Bonnie and Clyde’s… I wasn’t a Duchess kind-of-person. I’m not really a bar-type. I went to Bonnie and Clyde’s to dance but Lola’s in Ibiza was my first real experience. I don’t smoke anymore but they had a cigarette named after the club so you could buy a pack of cigarettes named Lola’s. You know how lesbians like to have their cigarettes! (Laughing) There was a mixture of people there. It wasn’t like… how do I say it… well, it was all types of people like artists and all different ethnic backgrounds because that’s what Ibiza was about. People could be amongst each other in that whole division and the women were very strong about wanting to have a space that was safe and that was exclusively theirs because that was a party-kind-of-an-island and if you went to say a club like the one called Pasha’s a lot of strange stuff could happen because it was just a free-for-all and of course there was a group of us who were like: This is not a free-for-all! And we weren’t interested in some acid-head guy coming up and disrupting but that’s the kind of stuff that would happen so it was just nice to be at a safe space that felt free. It was also one of those clubs that had a quiet area because sometimes it’s nice to just sit and talk with somebody! It’s not like everybody is just trying to meet someone to go home with for the night. You could actually have some real conversations going on and later you’d find out that during the day some of the women would have little meet-ups. Everybody was pretty much in the same age-range – eighteen, maybe a little older – nobody was trying to get with older women. Germany at that time though had clubs where that would happen – twenty-year-olds getting with sixty-year-olds. (Laughing)

GS: Were you living in Ibiza?

ROS: Yeah! Part of the time because I was in a work-study at Laguardia Community College and then I later went on to study at Richmond College. I studied special education. But I started going there through the work-study program. I went there I think from the age of eighteen to twenty-two? I’d go for about three months at a time.

GS: Wow! That’s amazing.

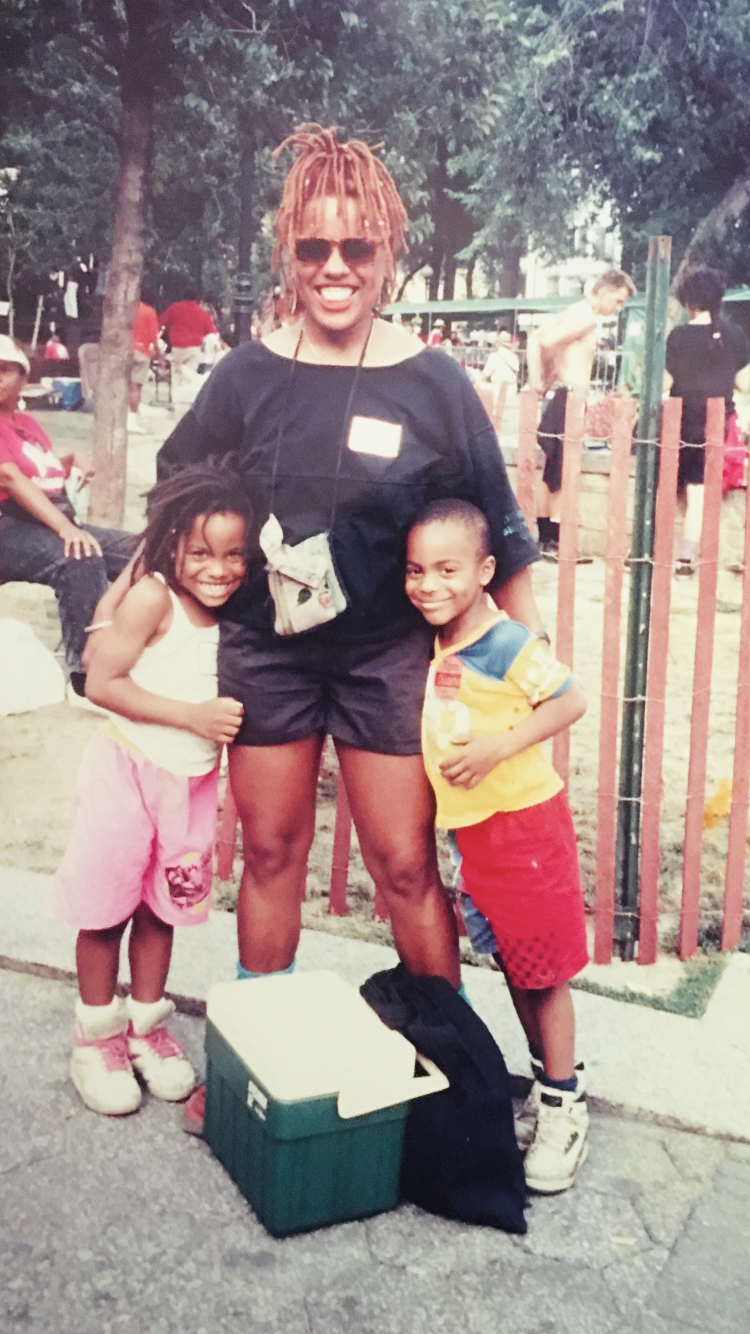

ROS: Yeah! And even when I did special education for my graduate program I still ended up liking to go there to explore how women interacted being in that particular place. That’s where I started having conversations with women who wanted to have children and started using artificial insemination. I didn’t have a particular girlfriend at that time but then after that… you know! Later on I’d been with someone for fifteen years and then we had our children together. But yeah, it was very diverse there. You’d meet people who came from Indonesia, women who were German, lots of women from West Africa and that’s actually when I met women from South Africa who had left, had gotten out of there. Not because they couldn’t be out at home but because they were not staying up in that apartheid regime going on. So, you got to see that. It was interesting because later down the line they would have weddings for lesbian couples and one who considered themselves trans – they carried on! They were open and accepting with that because they don’t think of it like that. What we might call an aggressive woman in this country – they weren’t looking at all that. They had no need to have a woman look a certain kind of way.

GS: Was there a sort of butch/femme dynamic there?

ROS: There was clearly that because you had people coming from different places so especially the women who were from Spain in particular had a machismo thing happening. So, yeah, they were really defined. But then you had the women from Indonesia who didn’t have that going on. Two women who were maybe looking very femme or two women who were looking more butch they could be together and they didn’t have that going on and there was no need for them to define it in that way. There was carry-over from what each person would see in their own culture.

GS: What an amazing first experience to have…

ROS: Yeah! My eyes were already pretty open though. Growing up we had two women living near us who ironically had the same last name as my family, but we were not relatives with one another and one of them was a well-known model in Italy and one of the sisters had a woman who she was in an open relationship with. There were examples of women just living with who they were. They didn’t have anything to say about it like, “Oh, this thing in Europe… that’s alright over there…” none of that kind of conversation went on. It was a funny little era for me. How do I say it… it was the ‘60s and there were just so many things going on, so many issues were happening. Civil Rights was going on, segregation and then forced integration of schools – so the issue of who was dating whom wasn’t so much a priority. Yeah, you knew who it was but you didn’t make a big fuss about it. Men, maybe, made more of a buzz about it because they tend to struggle. They want everything clearly defined, like, they gotta know who I am. So, that flamboyant behavior kicks in but it can also be very hostile. Guys who I knew when I was younger – gay men – I didn’t really have a lot of association with them because they were calling me the b-word and they didn’t really like women.

GS: Where did you grow up?

ROS: I grew up in Jamaica, New York.

GS: What was it like growing up there?

ROS: It was fine for me! I grew up in a house so we’d have house parties. Again, there were fine lines with certain things because it was all families. So, people would know what was going on but it wasn’t like you wouldn’t be invited somewhere because someone clearly knew that you identified as a lesbian or as a gay guy. Although there were a lot of people who… I wouldn’t call it crossdressing… but that’s as far as you could go at that time. There wasn’t any operation for men or women then. So, of course they made a distinction between a transvestite and someone who really preferred to be addressed as the gender they identified as… So, some people would deal with it and some people couldn’t deal with it. I was lucky. Certain boroughs of New York were tougher to be in. In the area I was in, in Jamaica, Queens, you wouldn’t see a gay man or lesbian get beat to a pulp in the park because it was so small, that particular area, that if somebody did that you would know exactly who did it. No matter what you may feel about them, it’s like, no. You cannot do that.

GS: How did you realize you were a lesbian?

ROS: Oh. I always knew. Since I was seven. I was very clear, you know, and by the time I got to be a teenager of course it was obvious and then prom at school with the girlfriend I had at the time so I’ve always been aware and comfortable in being who I am. I didn’t make up other words for it, I was clear. I liked some terminology but wasn’t sure if I really felt like that, I wasn’t sure why you couldn’t just say woman-who-loves-woman. I didn’t like certain names so much… I don’t like labels. I embrace others who feel as though they need that definition.

GS: Yeah. That’s amazing! You had a lot of self-awareness really young. Was your family accepting of you?

ROS: Oh, it was always fine. I think my mom had more problems when I was with my partner and we wanted children. She had more concern because she wasn’t up on how it worked with a donor insemination. She knew full well how it happens but she had a little bit of trouble understanding how we were going to explain it to the children. I just sat her down, you know, and posed a few scenario’s to her. She’s very open about things, so I could have that conversation with her. When she heard that she understood. She said, “Well. That’s what it is!”

GS: What was it like to have children at that time as a lesbian couple?

ROS: We didn’t even present it to the women’s community until the pregnancy took because many of them were of a certain age where they had their children and they had been in relationships with men or if they just wanted to have kids they figured it out. But they didn’t have the understanding of how donor insemination really worked. Some of them kind of understood in-vitro but not really because it wasn’t really a part of their life. So, they weren’t understanding that AI and in-vitro were totally different.

GS: Did you experience some backlash from the community or was it mostly just a lack of understanding?

ROS: It wasn’t so much backlash, they just had questions that they wanted to ask. And I just said: You know, we became informed early on, we learned what artificial insemination and choosing an anonymous donor was all about. Pregnancy is a pregnancy and I’m carrying the same way anyone else would carry. It was also just that it wasn’t something black women and women of color were privy too. It was the one area that even if they were a couple if somebody decided they wanted to have children, oftentimes the couple would end up splitting. Even if the donor was a friend it would end up affecting the relationship. I decided to go with an anonymous donor because I didn’t want anything interfering in our relationship. We were clear about that. That just baffled the women in the community. They didn’t understand how we felt safe with not knowing… But there were systems! We used one of the best sperm banks that they had probably in the state. You’d have to have blood tests to make sure you aren’t a carrier. If the donor is black you need to be mindful of Sickle Cell. If a person had that in their bloodworm, it wasn’t acceptable. If you’re a carrier or if you had it. Either way, if it was the donor or yourself you wouldn’t be candidates. If you want to go off on your own and figure it out fine but they wouldn’t let that happen at the sperm banks. The blood work was so intense. So, early on when we used to have the meetings every week at Salsa I brought it to the group because I wanted to enjoy our pregnancy with our extended family. We chose to do this.

GS: I think it’s really interesting how big of a part the community of Salsa played in your pregnancy. You were all so connected it was almost as though it was a community decision!

ROS: Absolutely! You should have seen it! Because I ended up having twins I needed a midwife who had hospital privileges and I was at a baby shower at Imani Rashid’s home literally on April fifth and the children were born on April sixth! So, my water and everything broke there! We were dancing, drumming and everything! My midwife said, “If by nine o’clock in the evening nothing is moving you’re going to have to come in.” We didn’t know who was coming out first and you don’t want to risk having one of the babies in the wrong position. So, of course we left the shower, right? (Laughing) Everybody who was left up in there got in their cars or whatever way they traveled and they were all waiting in the hospital lobby! (Laughing) They brought the food from the party and everything! The people in the hospital were like, “Who are all these people? What is all this?” They couldn’t imagine what was going on. Plus it was in Chinatown at Beekman Downtown Hospital. It was definitely a community endeavor and it continues to be that. My children are thirty-four years old and they still can’t go anywhere without everybody needing to know exactly who they’re with. There is a lot of affection. They’re just good people. Everyone really had something to offer and had something to help cultivate who my children are. Not just myself and my partner at the time. So, that’s what was really so beautiful about it. It’s such a close-knit community. We don’t have to hang out or see each other all the time. It doesn’t matter. If something is going on they’ll be right there.

GS: I really felt that at the panel you had at the New-York Historical Society. It was a powerful feeling to be in that room with everyone and to feel how strongly everyone is connected still.

ROS: Well, you know Donna Allegra? She made her transition… I don’t know if you remember her speaking that night. She wasn’t even sure if she was going to be there. But she stood up! And of course Chirlane McCray was there and spoke. They didn’t want her to be on the panel because they wanted the focus of the panel to be very specific. This particular panel they wanted to highlight something other than what was spoken about at the other events that took place the November before. I think that one in November was really the first one they did with the photos and what-have-you. It’s amazing to look back on ourselves and to realize how much we really did. It’s easy to forget how diverse it was and how many connections there were.

GS: How did you first get involved in Salsa Soul?

ROS: Um! I got involved with Salsa from going to Bonnie’s where I met Edwina, she had already known some of the women and so we were first getting acquainted and getting to know each other and she told me about social meetings, she went to on Thursday nights with a nice group of women. She said there were Black and Latina women and they met at the church over there on West 4th Street. And it was like right away. It was right away because we needed that, you know? It had come to a point in our lives where… because most of the people by that time had gotten into whatever they had planned to do like teaching, social work or whatever… they were doing that. So, with a certain age group they want to socialize and they want to be in an environment where they could come out. We were having conversations about how they are, what’s going on in their work places… Imani Rashid had been teaching fourth grade forever. She retired teaching the fourth grade. That’s why she was always connected to that and with the Kwanzas because she’s never not going to teach in a certain way. (Laughing) And how she implemented that at the school where she was at in Harlem working with those kids… everybody knew exactly who she was! And that’s another thing about a lot of us: We went into our jobs and people knew, you know, that we had women that we were in relationships with. At the lunch table that could be the conversation, you know, they are in there with you and they like who you are. It’s interesting when I hear some people ten years younger than I and listen to their stories about worrying about the job. Myself and people like Imani, Imani’s always been who she is and Cassandra Grant… It’s interesting because most of the women who did a lot of the chairing for Salsa they were comfortable with who they were. There wasn’t denial about it. And as time went on she could pull it in because she had so much respect from so many different communities. Her whole life wasn’t just about doing things with women. That’s the way we all were. We all functioned from within a range of communities. There was a wholeness about it.

GS: One thing Cassandra talked a lot about was how much love and support and friendship there was in the community but also how challenging it was sometimes to come to agreements on things.

ROS: Oh because it was passionate! People would bring their personalities in. I enjoyed doing workshops and they tried to pull me in to do board work but I wasn’t a board person – I couldn’t deal with the Board of Education, that’s why I left it and went on to do my performance work. If anything gets too fundamental… I can’t be boxed in like that. So, what ended up happening is they would go head to head in the board meetings. You can’t call yourself “Salsa” and have only one person on the board who is clearly a Latina woman and you’re acting funny about it. All the women were very strong-headed that came to the table with something to offer because especially when you’re dealing with a 501(c)(3) you want to make sure people know that this is not a little organization just trying to be something and just looking for a place to have a meeting you’re also a part of the change in where we’re living in particular in New York and nationally and then it becomes international. See, that was where we came in as musicians at the time. We brought the international aspect because we spent a lot of time performing. Four months at a time. And throughout Europe with… I don’t know if you remember Alexis De Veaux they had Flamboyant Ladies Theatre and there was the group Ibis… It wasn’t just about being entertainers it was the content of the work that we did and it was all very political so it wasn’t like we were going across the stage and people were tap dancing and you know what I’m saying! It wasn’t the follies. (Laughing) And then there was poetry that Alexis De Veaux was doing and that was a whole other story. But still women met at Salsa and we couldn’t sit there and just talk about who’s butch and who’s femme we were so much more than that. But you had to realize that for some of the folks still coming out it was a journey and they still had to get that part addressed and then learn what they were out in the world. You know, Cassandra is a complete intellectual and she didn’t care what you said you were, she’d say, “How are you going to work that when you have to go to the community and do something like giving a lecture?” You know? Like, what are you going to do with that? Where’s your voice in that? How are you going to get things passed to make sure all of our voices are heard? Some people would dismiss all of that, not even voting. So, there was bringing that into play. The significance of it.

GS: Yeah, it seems like the group had people in it on so many different levels of being out and experiencing acceptance of themselves and not only were you grappling with intense passionate group dynamics but each person was grappling with a whole set of issues on their own.

ROS: Mhm! Mhm. It’s a lot. It’s a lot. And you know you see the mental illness in the family of women and there were only a few lesbian therapists who had to carry that and they’d come to the meetings but they couldn’t really socialize and still be the therapist but they still would want you to know that there were lesbians who are psychiatrists and psychotherapists. But they couldn’t really do major socializing or anything because people didn’t want to feel like somebody knew what was really going on with them. But there was a lot of that. There was a lot of alcoholism, depression, and who’s strong enough to be able to address that in addition to coming out you know? So, sometimes that would get sticky also.

GS: Mm yeah that’s really hard. What types of workshops did you lead for the group?

ROS: Oh… I was into presenting on topics that had to do with maintaining our health and our awareness and paying attention to our family ties because a lot of the women were being diagnosed with cancer and things. Women would get diagnosed with advanced cancer and for it to be that advanced you know they weren’t getting checkups. Especially butch women they weren’t getting pap smears or breast exams. They did none of that. And then a woman like Sylvia Witts Vitale would kind of ease it in by talking about sex therapy and would talk them into going over to Joan Wakevitsz over at the Women’s Health Center on the Lower East Side. So, a lot of that was happening. I did my herbal studies with Arcus Flynn. I was already doing that work but I wanted to define it. She is wonderful. I love her. So, there were those kinds of things and then we did dance workshops with drumming.

GS: That’s wonderful! How did you get involved with music?

ROS: When I met Edwina! I’ve always been involved with music all my life professionally with trios, that’s always been a part of my dialect, but as far as really getting into combining the whole African drumming and the chanting… I was influenced by that in the ‘60s and then I met Edwina who is a drummer! And it was funny because I didn’t even know she was a drummer at first and she goes, “We’re going to go down to the pier and play a little bit!” And I didn’t know what she was talking about and I get down there and there is a whole group including students of hers and they were all drumming! And of course the drumming is on a level that I’m familiar with and I did my African dance and I was figuring out that culture and I just went off dancing! And she said, “I’ve been really wanting to do a group!” (Laughing) And so that made it very consistent. We put those chants to work because none of them knew the Yoruba dialect very well. I’d been listening to the Olatunji Drums of Passion forever so I knew all of that. So, since we were going to be doing African drumming and percussion and dance, the chanting was definitely necessary. You have to have an invocation and that wasn’t always something Edwina did in particular, but I liked the authentic Yoruba dialect. That was always an interest and finally came to be something that I could actually share and do in a more public kind of a way. Some of the women in Salsa studied with Edwina and went on to form some of their own groups. But the music thing has always been in my life. I was in the school band and chorus and we did plays and growing up out in Jamaica, Queens Count Basie and a lot of the jazz musicians had homes out there so in the summer they were very integral in having the youth come. They’d have barbecues and have us try out instruments and come up and sing on the mic. If you did choose to do that there was no reason to be shy about it because they didn’t really allow that to happen. It never felt like that. They weren’t going to have someone sing on the microphone who they knew couldn’t carry a tune. They would never put you out there like that. They would help you and teach you to use an instrument rather than saying, “That’s not how you do that.” These musicians themselves were very accomplished so they knew how to do that without making someone feel a certain kind of way. But I always had a strong vocal thing and I’ve always been interested in the energies of people like Sarah Vaughan and Nina Simon and Ella Fitzgerald. That’s who I looked at in terms of women and how they presented themselves on stage and how they came from the raw space. Their vocal abilities were amazing but also it wasn’t tight. You know? I liked that they felt comfortable sort of telling a story and walking back and forth around the stage and interacting with the musician who was playing. I was really attracted to that. For me that was like… yeah! And if you have the ability there and you can carry it over to cultural tradition like African music in particular then it was wonderful. It’s not just about presenting something well, you want to enjoy it also! You would get pleasure out of people enjoying something that you feel passionate about as well.

GS: Yeah, it seems like coming together with music was a really important aspect of the community.

ROS: Oh definitely! They would be just so open and at some point the music would get turned off at the party and it would be strictly live things happening! People would get out their drums and the shekere. Some people had a horn going and it was always in a house! We just did house to house! (Laughing) You know? And no one was thinking about it!

GS: Cassandra talked a bit about the challenges of going to lesbian bars in the city as a black woman and that often women had house parties to avoid racial conflicts. Did you experience it in that way too?

ROS: We had house parties because you grew up having house parties. Yeah, they had clubs out in Queens but those were really specific dance things that would happen but you didn’t go to the club as teenagers and so you kind of grew up with that! You cooked food, and you’d go to an age appropriate house party. Even with the Kwanzas… They were every night of Kwanza, every night at a different person’s house. That went on for a long time! And when that stopped happening… I don’t know what happened to be honest. We couldn’t sit and put our heads together a certain kind of way. At that point I wasn’t really going to Salsa per se. You have stages in your life, you know? You’re doing other things in your life. So, Thursday nights were a hard night to do anything after a while. I couldn’t go sit in meetings by the late ‘80s because, you know, we were working! We were doing what we were doing. But, you still connected. Something changed when the gatherings stopped being house to house. A lot of people didn’t want to say it… they were having a hard time saying it. At that point I had kind of stepped back in. But when I’d ask certain things to the group the room would get quiet and I’d say: Is somebody going to answer that? I didn’t understand why we were having Kwanza in The Center. There wasn’t energy in there for that. The only thing that would happen would be having the last day of Kwanza at Imani’s and then that stopped. It changed again but for a while the whole thing was happening at The Center.

GS: Right. And it didn’t have the same feeling?

ROS: No! Because then you’d have people coming in who really didn’t understand what the principles were about. We would go around and if somebody didn’t feel like speaking they would pass the unity cup in the other direction… You don’t want to say anything? Your energy is here, so that’s fine. But we would talk about each night and what the principle was and how were we going to let that principle manifest throughout the year for us as women of Salsa Soul. Or how are we going to take and implement that into our relationships with each other and in ourselves. Like for those who had a business we would make an effort to support what they had instead of going to the department store or something. Just those kinds of things. Some of what was happening though was a two-way kind of thing… I’m the kind of person who is comfortable wherever I go. I never feel out of place wherever I am. I could be the only woman in a room full of guys and I’m fine. I’m in a Yoruba group and sometimes there are no women in a meeting and it doesn’t matter because we’re all speaking the same language about the issues at hand. There would be situations sometimes at The Center where somebody would be at the door looking intimidated because there were so many black women. It was just different. There was a little club down the block from Bonnie and Clyde’s called the Bon Soir. Now that was where most of the Latina women went. Very seldom did you see an African-American women in there. Maybe someone from Panama! They had their little cliques going on too! I have a friend who’s from Panama but she’s one of those Panamanians who is very dark-skinned so they’re looking at her and when she starts speaking she’s very dramatic in her presentations of everything. You get intrigued by everything she says even she was talking about nothing. So, she would go in and start talking really rapidly and women would look at her… So, there would be that kind of weird rivalry because she’s Panamanian and they’re Puerto Rican. Very rarely did you see any Brazilians. Very little Dominican presence there yet. We’re still talking early ‘80s. So, sometimes if too many of us went to Bonnies at once they would try to get a little funky at the door. One time somebody did ask us if we were looking for the Bon Soir… Like, no. Nobody’s looking for the Bon Soir. We are where we’re at! Right here! I know Cassandra and others definitely had some confrontations. It was like West Side Story sometimes. I’ll just put it like that. (Laughing) And then it was like, well why are you trying to get in. You’re not going to prove anything with these people. I didn’t want to pay to get in someplace just to experience discrimination. Why are you begging at the door and going in some place where people don’t want you anyhow? You have to create your own space. Older women used to sit at the bar at the Duchess from the time it opened to the time it closed totally drunk, totally depressed… that was not a fun place to go in because that’s where a certain age group of women went and they would just sit up in there and be solemn. They tried to do something with the Duchess as time went on but… it was just dreary and drunk. Life is not easy. A lot of women resorted to alcohol in that time period. Maybe up in the Bronx you had people dealing with some harder drugs but in that area it was mostly women drinking until they were in a stupor. And they had nobody in their lives either so they were lonely. Women in Salsa didn’t want to do that. We were lively. That just wasn’t working. Now we’re in another age range and trying to get together. We need to start going back to one another’s houses. Bring what you bring, stay for a few hours and then leave. We need to connect because it’s vital for us who are still living. It can’t just be about people who have passed away.

GS: You’re so lucky to have this community because I think a lot about what it’s going to be like to age as a queer woman if I don’t have children and it seems like a lot of people in the community are going through illness on their own which is horrible.

ROS: How old are you?

GS: I’m thirty-two.

ROS: Oh! My twins are thirty-four. My daughter is married to a woman. Her and her wife have been together now for eleven years!

GS: Wow! Amazing!

ROS: Yeah! She’s that type! You know! One dances with Alvin Ailey and my daughter lives in Senegal right now. Her and another young lady who she grew up with who’s dad is in Senegal and her mother was from the South, here, they have a cultural art school in Senegal. They do cultural exchanges. She teaches as a dance therapist as well. She’s like how I am! I’d hear my calling and if it was time for me to be someplace I would go! I can’t imagine retirement. It’s not like I didn’t make money dancing or performing as an artist, I also worked as an occupational therapist for a while… I just knew how to manage my life and I didn’t need traditional structures set up for me. And look at what’s going on now! What is a 401K going to do for anybody now? But you know I understand that and I respect people who need that. I don’t need that security but I don’t appreciate when people have pushed me into a corner trying to convince me I did. I’m sixty-six now and do you hear me asking for anything? I had one accident I was in in 2015 but I don’t have any on-going issues. No high blood pressure, no diabetes, no bouts of depression, none of that. I have mental clarity! (Laughing) So, I lived my life the way I wanted to live my life and I enjoy what I do! I enjoy the various things that I do! I’ll always be connected to dance and I love doing home aid work because I like helping people. I own two businesses: Ancestral Roots African Loc Groomer which has been open from 1991 to the present and our family owned wellness business Holistic Healing On Wheels LLC which has been open from 2015 to the present.

GS: Roberta I know you need to go at two o’clock and I don’t want to keep you much longer but I did have one more question for you. Salsa is just such an amazing community and encompasses so much spiritually, politically and creatively. What is something that you would hope that the younger generation would take away from the work your generation did?

ROS: That they really show camaraderie. There’s nothing wrong with hashing things out… I mean, that room would get heated! But, it didn’t stay like that. You didn’t stop until there was a resolution. It wasn’t just about right or wrong. The camaraderie of it was important. You could beg to differ but if there was particular work that needed to be done it needed to get done. That’s the thing, they can’t divide themselves up because you’re not getting along. You can’t get along with everybody all the time but we didn’t cross lines. Crossing lines can be disruptive in any kind of organization. It can get really confusing. You don’t just haphazardly disrespect one-another’s positions on particular issues.

GS: Right. Yeah! And I’m sure it could get really complicated. Especially when you throw in the possibility for romantic interest and also intense political issues. I’m sure it could get messy but I like what you’re saying about respecting one another and holding friendship above all.

ROS: Mhm! Exactly. That’s the main thing. You have to have that integrity which we certainly did have. We did have challenging situations! We had a challenging situation with a sister who we loved so much who passed away and it got complicated because she was very complicated and then it took the strength of somebody to say, “You know what? We’re going to have to get together and figure out something around this because we can’t all just walk around like loose cannons about this person going. We need to resolve this and that person’s partner needs to understand that as well.” So, that got a little sticky. We don’t want that happening again.

GS: You still do have this strong network even to this day?

ROS: Oh, absolutely. I haven’t been to a lot of the AALUSC [African Ancestral Lesbians United for Societal Change stemming from Salsa Soul Sisters] events. They’re having important conversations and just because I’m a so-called elder it doesn’t always mean I can lend myself to a particular topic. It depends on what they’re going to be talking about. When real important things are happening, like what’s going on now, there’s no room for petty stuff, which is a good thing. What I do like is that AALUSC definitely has a great relationship with Cassandra.

GS: Are they continuing with a similar structure as you and the other sisters created?

ROS: It seems like it but maybe even more so! They’re working to really push the health issues and some of things that have come up we weren’t talking about! We weren’t having those particular health issues and they have a relationship with Circle of Voices and the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. AALUSC has a lot of good things going on. They have good referrals for people looking for therapy and they put it out there in such a way that it’s not like they’re singling someone out it’s just that the information is passed on if somebody needs it. See, we didn’t have that. We had therapists at Salsa but there wasn’t any material to pass out and there wasn’t any follow-up. Maybe someone would come and speak at a particular meeting about what they do and then they could figure out how to confidentially connect.

GS: Maybe it’s less taboo now too…

ROS: Absolutely. Mental illness will probably always be stigmatized though… (Sighs) Unfortunately. People do have a lot of shame about it.

GS: Well, Roberta I just can’t thank you enough for this and for all the work you’ve done in your life to create community.

ROS: You’re welcome.